___________________________

A note about Royal charity patronages re the passing of HM Queen Elizabeth II:

HM Queen had ~600 patronages. They were not all charities: many were parts of the military, cities, trade guilds etc.

Giving Evidence found that Her Majesty was patron of 198 UK registered charities. (The information published by the Royal Family about “charities and patronages” (their term) was incomplete, inconsistent and sometimes just wrong. So we had to construct that list: it took us about six person-weeks.) The charities of which HMQ was patron are listed here.

Giving Evidence’s data and analysis below show the types of charities of which the Royals are patrons. They are disproportionately large charities.

It is unclear how patronages are decided or how they are passed between Royals. It seems that the Royals decide amongst themselves: e.g., it was reported that Prince Andrew had returned some to the Queen to be redistributed. So presumably at least some of HMQ’s patronages – and possibly some of Prince/King Charles’ – will be redistributed (though it will be a bit difficult because the exits of Princes Philip, Harry & Andrew mean that there are fewer adult royals than previously.)

___________________________

Giving Evidence today publishes research about Royal patronages of charities: what are they, who gets them, and do they help? This fits within our work of providing robust evidence so that charities and donors can be as effective as possible.

In short, we found that charities should not seek or retain Royal patronages expecting that they will help much.

74% of charities with Royal patrons did not get any public engagements with them last year. We could not find any evidence that Royal patrons increase a charity’s revenue (there were no other outcomes that we could analyse), nor that Royalty increases generosity more broadly. Giving Evidence takes no view on the value of the Royal family generally. The findings are summarised in this Twitter thread.

We investigated this mindful that some donors help charities much less than they think they do. Some help a lot; some create so much work that dealing with them consumes the entire donation, meaning that their net contribution is nil; and some are even worse, creating a net drain. (Having been a charity CEO myself, I wrote an entire book for donors, about how charities really function and how donors can help them and avoid hindering them.) Equally, some well-intentioned programmes run by charities are great, some achieve nothing, and some are counter-productive and harmful.

Royal patronages can create costs for charities. For example, The Telegraph newspaper claimed that the Outward Bound Trust flew Prince Andrew, its then-patron, to New York to attend a fundraising event.

Charities often seem to think that a Royal patron will visit them, or enable events at palaces which they can use to attract press coverage or donors. In fact, most UK charities with Royal patrons did not get a single public engagement with their Royal patron last year: 74% of them got none. Only 1% of charities with Royal patrons got more than one public engagement with them last year. {In this video, it transpires that Kate hasn’t visited one of her patronee charities for eight years.} Some got many more, but they are mainly charities set up by the Royals. We found that same pattern when we analysed a three year period, 2016-19. Charities set up by the Royals are 2% of the patronee charities but last year got 36% of the Royals’ public engagements with patronee charities. (Later, Prince William took over two patronages from the Queen and Prince Philip. One of those charities had had one official engagement from their Royal patron in the last ten years: the other had had none in ten years. Data here.)

Charities cite various benefits of Royal patronages e.g., on staff morale, on beneficiaries. We do not deny these. But we are trying to do science, so needed reliable and comparable data about the large number of charities that we needed to analyse. The sole such data are revenue, so we used that. The potential to raise a charity’s revenue appears to among the Palace’s criteria for selecting charities.

Just by looking at graphs (see below) of the revenue over time of the patronee charities versus that of comparable charities it is looks as though revenue is not affected when a Royal patronage starts.

We also looked in much more complicated ways. We used several sophisticated analytical methods: econometric regressions using various combinations of comparator groups and outcome variables. None convincingly found an effect.

In the videos below, we explain what we researched, why, how, and what we found. We had three research questions: what are Royal patronages; which charities have them; and what difference do they make?

Charities seem to matter to the Royal family. ‘Charities and patronages’ is the first permanent item on the Royal website below an article about the Monarch.

As well as finding no evidence that Royals bring revenue to their patronee charities, we also found no reason that donors should assume that a charity with a Royal patronage outperforms its peers. Take air ambulances. The UK has 21 air ambulance charities, each serving a different ‘patch’. The ones with senior Royal patrons are: Cornwall (Camilla: Duchess of Cornwall), London (William: who lives in London), Wiltshire (Camilla, who has a house in neighbouring Gloucestershire), and Yorkshire (Andrew: Duke of York). It seems likely that these selections are driven less by quality than by history and geography.

We found no evidence that a concentration of Royal patronages of charities in a geographic area increases the generosity of people in that area. (We compared English regions on (i) the number of Royal patronages they have, and (ii) the proportion of people who have given recently). And looking internationally, we found no evidence that a resident Royal family makes a nation more generous. In short, we looked from many angles, and did not find evidence of a beneficial effect from any of them.

Our research had to start by identifying which Royal is patron of which charities. This turned out to be vastly more complicated than one might imagine. The data published by the Royal family about patronages doesn’t distinguish between charities and other entities (cities, parts of the military, private sports clubs, etc.), and it is often inconsistent, incomplete, unclear, and wrong. The weblink on the Palace’s website for one of Prince Harry’s patronages went not to the charity but to a porn site. Prince Charles’ website has a list of his patronages. Buckingham Palace also publishes a list of his patronages. They’re not the same list. It took us six full weeks to construct a defensible list of which Royal is patron of what.

The UK Royal family has 2862 patronages, of which under half (1187) are with UK registered charities. Most charity patronees (1067) have a single Royal patron though some (123) have multiple Royal patrons. They carry various titles, such as patron, honorary patron, president, honorary fellow, and, in one case, Companion Rat. The charity patronages are very unevenly spread: half of the single-patronage patronee charities have Prince Charles, Princess Anne or the Queen who have 532 between them.

The patronees which are UK registered charities are diverse. But they are concentrated in ‘environment and animals’ and ‘culture and sport’ – relatively uncontroversial causes. The sectors with fewest Royal patronages are housing, employment, social services, and religion. They are disproportionately large: their revenue is (on average) nearly 30 times larger than the average UK charity. And they are disproportionately in London, the South East and South West of England – where the Royals’ main residences are. More deprived regions seem under-represented.

Royal charity patronages also raise a question of public expenditure. The Royal family costs the taxpayer – on the sole estimate we found which includes the cost of their security – £345m per year. If we take public engagements to indicate their workload, 26% of their work is for their patronee charities: equivalent to around £90m per year. If that produces no discernible benefit, it may not be good value for money. On the other hand, if Royals do help patronee charities, it is legitimate to question the process and criteria by which that publicly-funded benefit is distributed, which are currently not clear.

Our research was funded by the Belgian Red Cross, Flanders, which has a demonstrated commitment to producing high-quality evidence to inform decisions of operational entities, in the Red Cross network and beyond. Giving Evidence’s Director Caroline Fiennes is on a board of the Belgian Red Cross, Flanders.

We hope that our research enables more evidence-based decisions by patrons, donors and charities, and hence more effective help for their intended beneficiaries.

_______________

The research involved various assets and methods including:

- A database with 3 million entries. Every charity in England and Wales; every item in every set of financial statements it had reported in each of the last 25 years.

- Many data-sheets each with several hundred thousand rows, e.g., to match every charity in the UK to its Parliamentary constituency; a list of all UK Parliamentary constituencies categorised by region; and data on the population of each constituency. We made this in order to compare the geographic distribution of patronee charities with that of the UK population, and of the UK population of charities (see chart below).

- Six methods of two-way fixed-effects analyses. These are described in detail in the report.

_______________

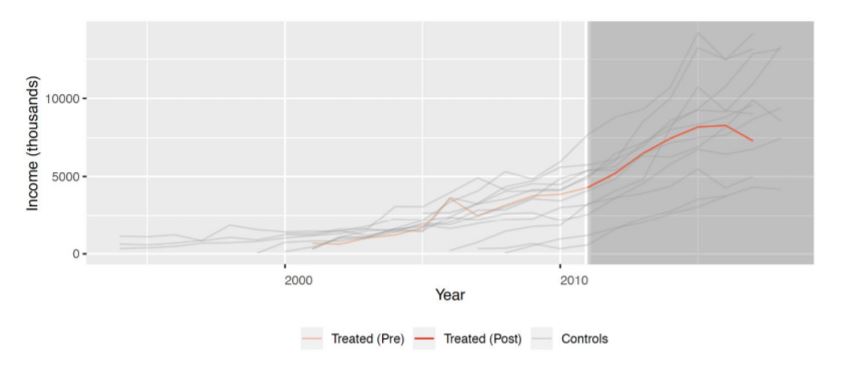

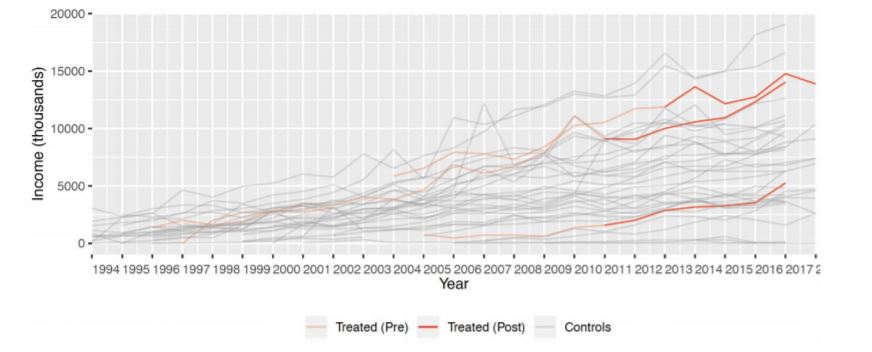

Below is the revenue of various UK air ambulances over ~20 years. It compares the revenue of those which got Royal patrons (in red) versus that of those that did not. (Air ambulances are one of several sets of ‘natural comparators’ that we used in our analysis.) Below that, we do the same for children’s hospices, some of which also started Royal patronages during the period of our financial data and most did not. The graphs for the other groups we analysed are similar.

These graphs indicate (but do not prove) that nothing very spectacular happens to charities’ revenue after a patronage starts. Any effect of Royal patronages on the revenues of patronee charities in those groups seems small or nil.

This graph shows the split of charities with Royal patrons* split by sector, compared to that of all UK charities. It shows that environment and animals are ‘over-patroned’ and religion and housing are ‘under-patroned’.

This graph shows the split of charities with Royal patrons* split by geography, compared to that of all UK charities. It shows that London the South-East and South-West are ‘over-patroned’, and that everywhere else is ‘under-patroned’.

*The graphs above show charities with one Royal patron, and where patronages where the patron’s role is called Patron, Ambassador or President. We suspect that positions with other names, e.g, honorary positions, may denote a different type of role. (This was among the questions we asked of the Palace which it did not fully answer.)

The graph below shows the size (revenue) of charities with Royal patrons* compared to that of all UK charities. It shows that patronee charities are much larger than most charities, on average: 30 times larger, and the charities with multiple Royal patrons are on average 80 times larger.

We were not able to analyse the effect of Prince Andrew stepping back from his public duties. He stepped back from all 60 patronages of UK registered charities simultaneously: that may be enough to detect an effect e.g., on revenue. That detection will require some data for ‘after’ his involvement ceased: our analysis was too soon after it. The effect on press coverage may be visible in a few months’ time; the effect on revenue may be visible once there are a few years’ of reported accounts.

We could not split out the effect of individual Royals because the numbers are too small. For example, at the time of our analysis, Prince Harry had eight charity patronages, Kate had nine, Prince William had 12: sets that size are just too small to analyse.

_____________

Introduction to our analysis of Royal patronages of charities:

What are Royal patronages of charities?

Which charities have Royal patrons?

What difference do Royal patronages make?

Pingback: Research Finds Royals Don't Contribute As Much to Charities One Might Think - CelebsYou

Pingback: Research Finds Royals Don’t Contribute As Much to Charities One Might Think – Ujagar 365

Pingback: The Great Royal Charity Scam… | revoltingsubject

The method is explained in great detail in the report. It included six types of regression analysis, plus some other analyses. Some showed no evidence of effect; some showed evidence of no effect.

You will know that one data-point doesn’t disprove a trend.

Accordingly, this report shows that if the British royal family disengage from charity work, the taxpayers save 90 million pounds.

Pingback: “Royal Patrons” of Orders of Knighthood: do’s and don’ts – Nobiliary law – Adelsrecht – Droit nobiliaire

Pingback: Being Royal v Being Philanthropic – Ivy Barrow

thanks for the good work.