Giving Evidence’s Director Caroline Fiennes writes the ‘How To Give It’ column in the Financial Times. These are the articles.

Why charity should begin in the science lab (April 2016)

Not all charities are good causes. This may sound surprising, because we’re used to thinking of them all as being somehow virtuous, but they vary in their effectiveness. Smart donors know that good intentions alone aren’t enough.

Take, for example, the important goal of reducing cases of diarrhoea in Kenya — a major cause of child death. One solution is to provide chlorine at the water pump for people to add to their water when they collect it. Another is to deliver chlorine to households so people can add it there. Read more.

Choosing causes and charities: look for problems that are big and under-funded (January 2019)

My financial resolution for this year – as flagged by FT Money earlier this month – is to review the charities in my will.

I wrote my will a while ago in some haste, and chose the charities in the way that I suspect many people do: I listed the causes that I care about, then wrote down the first charities working on those issues that came to mind.

This is a pretty rubbish process, as we shall see. Read more.

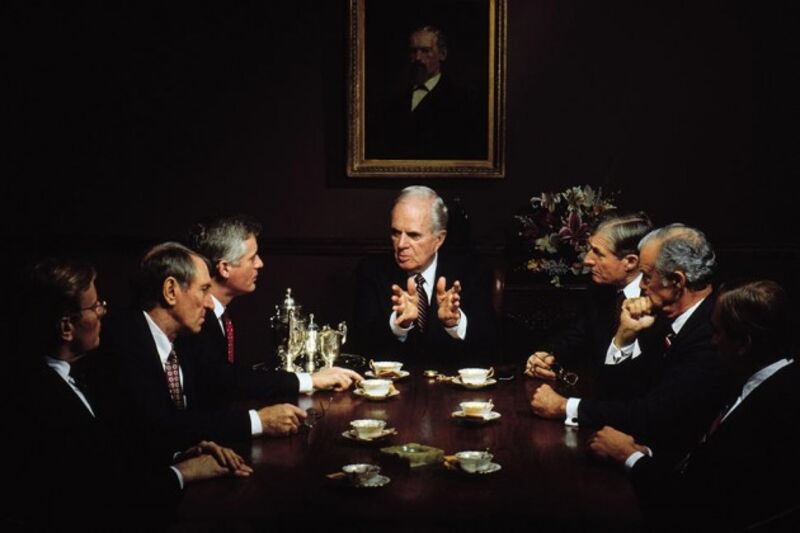

Lack of diversity in foundation boards is a problem (Oct 2018)

Every donor who sets up a charitable foundation needs a board. And every company  starting a charitable programme needs to determine who will make the decisions about what it does and whom it supports.

starting a charitable programme needs to determine who will make the decisions about what it does and whom it supports.

There seems to be a major problem with these boards. In the UK, 99 per cent of foundation board members are white, according to data published this summer by the Association of Charitable Foundations. Only three per cent of foundation trustees are under 45 years old. Sixty per cent are retired. Two-thirds are male. They are “drawn from a narrow cross-section of society: white British, older and above average income,” the report says. Read more.

Charities (gasp!) using and producing sound evidence (August 2018)

Anne Heller has done something that I had never previously seen in my 18 years in the non-profit sector. She identified a social problem, scoured academic literature to find a solution, and then set up a non-profit to implement it. That approach sounds jaw-droppingly obvious, but it is in fact very rare for a charity to design itself around existing evidence.

Ms Heller had worked for the city of New York when Michael Bloomberg was mayor, running shelters for homeless families. She noticed that about 10 per cent of the families who use the shelters returned repeatedly. In other words, the services which the shelters provided were not solving these people’s problems. Read more.

With all due diligence: Claims made by some ‘impact investments’ do not stack up (September 2018)

Demanding a financial return often reduces the social benefit rather more often than impact investors let on

It is a beguiling offer — an investment that can produce a financial return and also a social /

It probably does happen sometimes but certainly not for every impact investment product. Investors must be on their guard.

The impact of something is the difference between the world in which that thing happens versus the world in which it does not. So assessing impact means considering what would have happened without it.This is how to assess the impact of anything. For example what would have become of you if you had not been educated? What would have happened to Europe without the reparations demanded from Germany after World War I? Read more.

Charity begins with admitting we got it wrong (August 2018)

We need to be scientific and fearless about assessing whether proposed solutions work

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation seems to have wasted six years and $1bn, having initiated a programme to improve teaching effectiveness in US schools. An evaluation released last month showed that it had a negligible effect on its goals — some of them worsened — which included student achievement, access to effective teaching and dropout rates.

Much the same happened to Ark, the UK-based charity founded by the hedge fund industry. It created and co-funded a programme in 25,000 schools in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, supporting the government to improve school performance. It was based on sound research about how to reduce teacher absence, improve teaching and create more accountability through school inspections. Ark has worked on it since 2012. Read more.

The second best thing to give to charity is feedback (May 2018)

Donors can encourage charities to seek feedback

Oxfam’s UK chief executive announced his resignation last week, after a spate of damaging allegations of abuse by the charity’s frontline staff in Haiti. But would the whole issue have been avoided if Oxfam had had a decent and open process for hearing from the people it seeks to serve?Listening to intended beneficiaries can vastly improve a charity’s effectiveness, because they often understand the reality on the ground better than those who design a charity’s programmes.

The Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) helps Americans with criminal convictions find and retain work and continually collects feedback from the people on its programmes. Its induction class in New York City started at 7am. The feedback system found that many participants lived so far out of town that transport near their homes had barely started at the time they needed to leave home to reach the class. Nobody in CEO could really remember why it started so early; simply by shifting the class an hour later, CEO saw satisfaction improve with no detrimental effects. Read more.

Empowering the poorest of the poor (April 2018)

The global ‘gig economy’ is awash with downtrodden but effective campaigners

The council wanted them out. The Grand Parade area in front of Cape Town’s City Hall needed to be clear for filming one day last month, so the market traders who have their stalls there would need to disappear. There have been traders on that stretch of ground for hundreds of years and, for them, a day without trading is a day without income.

needed to be clear for filming one day last month, so the market traders who have their stalls there would need to disappear. There have been traders on that stretch of ground for hundreds of years and, for them, a day without trading is a day without income.

But they had taken a lesson from the previous month. In February, they were to be removed for the then-president Jacob Zuma’s “state of the nation” address, as the Grand Parade area might have been needed for a helicopter landing. Read more.

Donors left empty-handed on charity data questions (March 2018)

Judging by my inbox, there seems to be huge demand for advice about which charities to support. As donors have followed the turmoil around Oxfam, Save the Children, Kids Company and others before them, they want decent independent analysis along the lines of the data that rating agencies provide for bonds or Which? does for fridges.

There isn’t any. Read more.

Charities should have kept Presidents Club donations (February 2018)

Among the many issues to have arisen from the FT’s exposé of the Presidents Club is whether charities that received donations from the controversial event did the right thing by returning the money.

Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity was one of the first to announce it would return funds promised to it from this year’s dinner, as well as previous years, citing the “wholly unacceptable nature of the event”. The charity said it was “shocked to hear of the behaviour” and would “never knowingly accept donations raised in this way”.

The Charity Commission for England and Wales has already launched an inquiry following allegations of lewd comments and groping at the event. However, a YouGov poll this week found that two-thirds of people thought recipient charities should keep the money (one in five said the charities were right to return it, and the remaining 13 per cent were unsure). Read more.

Charitable foundations: There’s an argument for spending it fast (January 2018)

Growing number of funds take a shorter-term approach

Having spent its entire war chest of $100m, the Skoll Global Threats Fund closed last month. Jeff Skoll, eBay’s first employee and first president, created the fund to “make progress against five of the gravest threats to humanity” — climate change, pandemics, water security, nuclear proliferation and conflict in the Middle East — and gave it eight years.

It is one of a growing number of foundations which are “spending down” and disbanding. Atlantic Philanthropies, set up by Chuck Feeney, co-founder of Duty Free shops, finished spending its $8bn in 2016 and will close in 2020. A foundation created with public donations after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, closed in 2012. Read more.

Try not to judge a charity by its admin costs alone (December 2017)

Producing the kind of data donors would like is hard and expensive, but not impossible

We kept overheads low, boasts Camila Batmanghelidjh in her book published last week  about how and why Kids Company, the charity she founded, collapsed in 2015.

about how and why Kids Company, the charity she founded, collapsed in 2015.

Perhaps skimping on administrative costs was a false economy. In the book she also says the charity kept paper records for the 36,000 children and young adults it claimed to support, which were “stored in 80 cabinets”. It hardly sounds ideal. Read more.

Make one donation, get one free (December 2017)

Making a big gift to draw other donors is only useful if the charity is highly effective

The practice of donors offering to “match” gifts made to charities they support has become common in the charity world. In the run-up to Christmas, many have been offering to double donations. In the recent Challenge Campaign, for instance, money given to selected charities was doubled by the Big Give, set up by Sir Alec Reed, founder of Reed, the recruitment firm.

Others schemes propose different deals: one donor was offering to give $2 for every $1 given on Friday to Charity Navigator, a charity rating agency; while PayPal will add 1 per cent to all donations made through its platform until New Year. Read More

How to give to education (September 2017)

Malala Yousafzai starts at Oxford university next week. The Nobel Peace Prize, which she shared at the age of 17, was for her work promoting the right of all children to education. Many people give money in pursuit of that aim, so it’s reasonable to ask what we know about improving education, particularly in less developed countries.

The answer is surprisingly little. Rigorous evidence about both primary and secondary education is rather sparse, though primary education is better studied. Very few programmes have been tested often enough, and in enough places, to give confidence about their effectiveness. Read more.

Donating $100m is just like donating anything else (September 2017)

So, $100m is a sizeable donation. And one charity is in line to scoop the lot. The John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, a $6.5bn foundation based in Chicago, is looking for “a single proposal that promises real and measurable progress in solving a critical problem of our time” to which it will donate $100m.

More than 2,000 organisations applied to the aptly named 100 & Change campaign. Eight have been shortlisted. Foundations normally make their decisions behind closed doors (and are much criticised for it) but MacArthur is running the selection process in full public view. The single winner will be announced in December. Read more

Godzilla charities threaten to overwhelm smaller rivals (July 2017)

Death comes rarely to big charities. The Charity 100 Index lists the largest charities in the UK, and of the 100 which it listed last year, 94 have reappeared this year. (For context, the UK has more than 200,000 charities.) The top 10 biggest charities were exactly the same as the top 10 last year, though the order has re-shuffled a bit. The top three — Nuffield Health, Cancer Research UK and the National Trust — were not only the same last year but have been the top three now for 13 years consecutively. Read more.

Three ways to tell if you’re giving effectively (June 2017)

This article describes three methods for assessing the effectiveness of giving. If many donors did this, and published the results with descriptions of how they give, we could build up a picture of how best to give in various circumstances. This ‘science of philanthropy’ is described in Caroline’s article in the scientific journal Nature. Giving Evidence recently published analysis of one of the types described below, with the ADM Capital Foundation, based in Hong Kong, published here.

Analyses to check that your donations have the maximum impact

Warren Buffett notices a feature of philanthropy that makes it more difficult than running a business. With philanthropy, he says, “you can keep doing something that doesn’t make any sense and there’s no playback from the market”. So how do you know if you are giving well? Read more.

Help the homeless: don’t give your spare change (April 2017)

Support homelessness charities and send your money to where it’s really needed

It is the classic Venn diagram: not everybody who is homeless is a beggar, and not

everybody who is a beggar is homeless. Rough sleeping is different again: rough sleepers are a small proportion of homeless people; some of them beg and some don’t.

Crisis, the homelessness charity which this week marks its 50 birthday, says 114,780 people were homeless in England during 2015-16. Perhaps as many as 34,500 people sleep rough in England in any year; around 4,000 a night. Crisis says that for every rough sleeper, there are 100 people in hostels, and 1,100 households in bed and breakfasts and overcrowded accommodation.

So what is the right reaction when someone in need asks you for money on the street? In an interview with an Italian magazine last month, Pope Francis suggested the answer was to give without hesitation. But many charities beg to differ. Read more.

Breaking the hunger cycle for the price of a bus ticket (March 2017)

Modern philanthropists adopt an evidence-based approach

The Christian tradition of giving things up for Lent comes, it is said, from making a virtue of necessity. Last year’s harvest, gathered in the autumn, would have sustained people through the winter, but by March and April, supplies would be running thin. Rationing and starvation were common. Hence, religious blessing was given to abstinence and  forbearance during these bleak months.

forbearance during these bleak months.

The cycle persists. About 300m people globally still have an annual “hungry season” before the new crops are ready. They’ll often skip a meal each day, which is particularly dangerous for pregnant women and young children because it irreparably damages cognitive development. Yet this suffering can be prevented for just the price of a bus ticket. Read more.

Why are there so many charities? (January 2017)

Donors encourage smaller organisations – but does that help beneficiaries?

There are 165,000 registered charities in England and Wales alone, which people often say is a lot. But is it? Moreover, it is too many? It’s not clear what “the right number” of charities actually means. By comparison, the UK has nearly 30 times as many c ompanies.

ompanies.

The reason there are so many charities stems from the economics and dynamics of the charity sector, which are worth understanding as they’re completely different to those underpinning how businesses work. When entrepreneur and former mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg, embarked upon philanthropy, Richard Riordan, then mayor of Los Angeles, advised him: “You are going into another world. It’s like going to Mars — [there is] a different logical and mathematical system.” Read more.

Don’t spread the love (December 2016)

One big donation will be more effective than several smaller ones

Would you prefer to receive one big present this Christmas, or lots of little ones? Your

inner child will tell you that holding out for one major gift that you really want is often the best choice. And the same goes for charities, who will benefit from one big donation this Christmas rather than numerous small gifts.

In my last How to Give it column, I told you how the insurance group Aviva has been inviting public involvement to give away £1.75m to “at least 800” non-profit organisations. Yet the evidence suggests that making numerous small gifts is not a good idea. Read more.

When donors cost more than they give (November 2016)

Some charitable donors are a net drain: they cost organisations they seek to help more than they contribute. Others come pretty close, costing nearly as much as they give.

When I was a charity chief executive myself, I personally handled a gift from a foundation. Dealing with it before and after we received the money cost us 90 per cent of amount it gave us.

Aviva’s Community Fund may be another salutary example. It has recently been inviting “community projects” to apply for a share of £1.75m, and says it will fund “at least 800” of them. We’ll return to the question of whether splitting funds into numerous small grants is a good idea. For now, let’s focus on the fact that Aviva’s applicants must get loads of people to vote for them in an online poll. This is partly a popularity contest; nearly 4,000 organisations have registered. Read more.

How come so much of your donation to medical research is wasted? (September 2016)

The news that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla are putting $3bn towards “ending all disease” has renewed the spotlight on the giving of Silicon Valley’s wealthiest. They are not alone in their enthusiasm for medical research: it is also the most popular target of charitable giving in the UK.

There is a problem, however: about 85 per cent of medical research is wasted. That’s equivalent to 22 of the 26 miles which people run in marathons to raise funds for research into cancer and other conditions. Globally, that waste costs around $170bn every year. Perhaps many of us suffer with conditions which could have been cured if those funds had been spent more productively. Read more.

Be a toilet roll philanthropist (May 2016)

Toilet roll seems an unlikely emblem of effective philanthropy. Yet I’ve heard of a donor

who specifically funds loo rolls in London museums and galleries on the simple grounds that this kind of donation is both necessary and tough to fund.

Many donors want to fund the glamorous stuff: front-line programmes, identifiable projects and new buildings being prime examples. To do so, many “restrict” their gifts to those items. The main problem with this approach is that donors generally all want to fund the same things — none of which include loos, core staff or rent. Read more.

What would have happened otherwise? (May 2016)

The purpose of a charity’s work — and your support for it — is to create a benefit beyond what would have happened anyway. This, of course, sounds obvious but (as my home discipline of physics powerfully attests) it’s fine to state the obvious as it can throw up some unexpected insights.

Charities are under considerable pressure to “demonstrate their impact”, yet few examine or recount what would have happened without them. “What difference does your work make beyond what would have happened anyway?” is perhaps the single most useful question that donors or trustees can ask. Read more.

Further articles are here.

More on Giving Evidence’s work is in the videos below, and here.