Demanding a financial return often reduces the social benefit rather more often than impact investors let on

A version of this article first published in the Financial Times in September 2018.

It is a beguiling offer — an investment that can produce a financial return and also a social /

The impact of something is the difference between the world in which that thing happens versus the world in which it does not. So assessing impact means considering what would have happened without it.

This is how to assess the impact of anything. For example what would have become of you if you had not been educated? What would have happened to Europe without the reparations demanded from Germany after World War I?

Establishing what would have happened otherwise, the counterfactual, is sometimes impossible as in the reparations example. In those cases we have to make reasonable conjectures based on everything else we know. Sometimes it is possible – though it may be complicated. This is a whole branch of social science.

Rigorous use of those scientific methods shows that at times, the impact of something is not what we imagine.

Take a remedial education programme for children in KwaZulu Natal in South Africa, for example, where school lessons are in English after the fourth year of primary school. Because this is a foreign language for many poor children, they fall behind. During the programme, the children’s test scores increased by about half. But what would have happened without it? When researchers studied it properly they found that children who had not taken the remedial class had also improved — and by the same amount. So the programme would appear to have had no impact. So the programme achieves nothing.

There are many such cases. I rehearse all this here because impact investors should make good use of this rigorous science to check whether an ‘impact’ investment does in fact have a positive impact. We are often misled.

Most impact investment propositions involve charging for a product or service, in order to create a revenue stream. But charging can reduce the social / environmental benefit. This is true of every case where I have examined the underlying research.

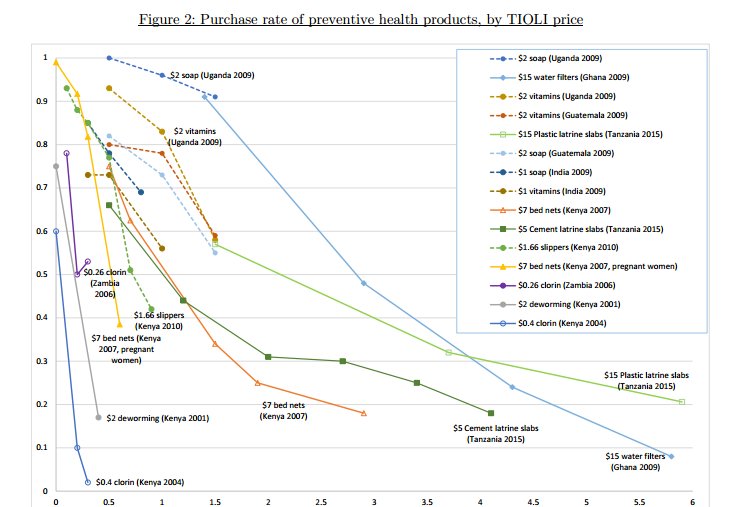

Take insecticidal (anti-malaria) bed nets. But research clearly shows that most people will not pay. As soon as there is a charge for the bed nets, the demand drops dramatically.

Nor it is the case – as you might imagine – that people who have paid for bed nets are more likely to use them. Usage, and therefore impact, does not depend on whether people paid for the nets. If your goal is preventing malaria, by the time you have made the nets and shipped them to where they need to be, you should just dish them out for free.

Solar lights in poor countries are another example. You might think people would pay to have light in the evening and cleaner air indoors because they are not burning kerosene. But a study of more than 1,400 households in Kenya found the take-up fell by 70 per cent when they were charged the market rate for the solar lamps. Even when the price was heavily-discounted, demand went down by 30 per cent. Making people pay had “no significant increase in children’s study time nor shifts to more productive time use for adults.”

We see the same thing with other preventative health products, such as disinfectant to remove contaminants from drinking water. Demand declines steeply as soon as users have to pay. So the social goal conflicts with the financial return.

There is evidence from South Africa that demand for water, particularly drinking water, is inelastic, for poorer households. Demand does not go down as the price rises. Water is essential, so price is not a good way of reducing demand, especially if demand reduction is a public policy goal, as it has been recently in drought-stricken Cape Town. If poor households have to pay a high price for water, it raises the question of what they are doing without in order to pay for it.

The pattern holds also for other goods, such as school uniforms. In Kenya, even though uniforms cost only about $8, charging for them significantly reduce school attendance.

But you could say that if charging for school uniforms in order to produce an investment return reduces demand that might be fine because the revenue they raise can be re-used, unlike grant finance which can only be used once. Details matter here and we need to be careful. That argument only works if the investment income is in fact recycled often enough to offset the reduction in demand. I have never seen an analysis of whether it is. Worse, it may be the poorest people who are frightened off by having to pay for a uniform, and serving them may produce the greatest ‘impact’.

Or you may argue that impact investors should provide products such as solar lamps or school uniforms at a discount to those who can pay a bit, and philanthropy should provide them for free to people who cannot pay at all. That would be fine, although it is hard to means-test the distribution of all the items I have listed.

Another response is to provide cash to poorer households so that they can buy what they need. Or use philanthropic money to provide incentives, or what behavioural economists call ‘nudges’, to encourage take-up. This method been shown to work in India where vaccinations for young children require multiple visits to a clinic and poor families often drop out. Researchers found that offering parents a kilo of lentils if they completed the course increased immunisation rates six-fold.

There is, then, sometimes a conflict between social return and financial return. Prospective impact investors need to look at the research underpinning the proposed interventions and question how robust it is.

Last year, my organisation, Giving Evidence, looked at the impact claims – and the evidence behind them – made by various social enterprises for a client who was an impact investor client interested in Uganda.

First we found the sectors which seem to be highest priority there, as identified by the public, government, think tanks, or other observers. These were education, health, access to finance, agricultural productivity, public sector management and employment opportunities. Then we looked for an example of social enterprise in each of the six sectors, which, as a mark of quality, had had investment from two well-known impact investment funds. Most of the six operated in East Africa, though for two sectors we had to look elsewhere.

Of those six, three provided no evidence of impact at all in their public materials. Either they have the evidence but are not publishing it, or they don’t, in which case ‘impact’ investing in them is flying blind. A fourth social enterprise presented no evidence but did have a sensible-looking study underway.

A fifth cited a single study. That is probably better than nothing, but can be dangerous because it is very common that multiple studies into precisely the same thing find different answers, just by random chance.

The sixth social enterprise was the outlier, citing several high-quality studies. This was the social enterprise we looked at for ‘public management’. The two impact investment funds had no investees working on this in East Africa, so we ended up looking at one called Dimagi founded in the US. Dimagi has created a mobile technology, CommCare, which can improve service delivery (e.g., by health workers) in underserved communities, and is used in over 50 countries globally. It is unusual in the social investment world: it was founded out of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which might explain why it has better evidence that most do. That background is obviously highly unusual.

Six organisations is not a big sample, but those impact investment opportunities had alarmingly little evidence to back up their claims of social or environmental benefit. I would encourage investors and the professional funds to do what we did, and look at the research behind those claims.

I’m not saying that no organisations at all produce both social (or environmental) benefit as well as investment returns. But it is clear that not everything which is touted as producing public benefit and private benefit actually does do so. Would-be impact investors should be cautious, and read the rigorous research.

In short, caveat emptor: if it sounds too good to be true, perhaps it is.

Pingback: Impact Investments Don’t Always do Good - BLKISH

Pingback: Letter in The Economist about anti-malarial bednets |