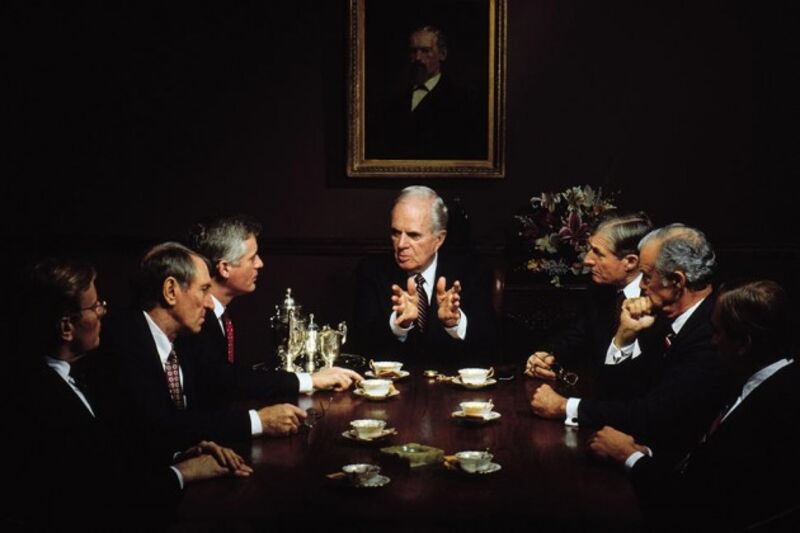

Lack of diversity is a problem for foundations and grant-making committees

This article first published in the Financial Times in September 2018.

Every donor who sets up a charitable foundation needs a board. And every company  starting a charitable programme needs to determine who will make the decisions about what it does and whom it supports.

starting a charitable programme needs to determine who will make the decisions about what it does and whom it supports.

There seems to be a major problem with these boards. In the UK, 99 per cent of foundation board members are white, according to data published this summer by the Association of Charitable Foundations. Only three per cent of foundation trustees are under 45 years old. Sixty per cent are retired. Two-thirds are male. They are “drawn from a narrow cross-section of society: white British, older and above average income,” the report says.

When a friend of mine began running a foundation outside Europe, she discovered that several people listed as trustees were, in fact, dead. The dead are weirdly important in philanthropy – for example, they are major donors – but they’re not meant to be making decisions.

It is barely any better in the US. Though foundation boards there are nearly balanced on gender (55 per cent male and 45 per cent female, according to research by BoardSource), only 29 per cent of trustees are under 50 years old. Some 85 per cent of board members are white, and two out of five foundation boards are entirely white.

This matters. Perhaps not coincidentally, 900 of the 1,000 biggest foundations in the US spend less than half of their budget on underserved communities, according to the US National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy.

Board diversity seems to affect performance. We can’t see this directly in the performance of charitable foundations because, as I’ve lamented in this column before, there is too little reliable data to draw any useful conclusions. But the pattern is clear elsewhere.

For example, research about the governance of US banks published in May by economists at Hamilton College in New York state, and at the Federal Reserve, found that gender diversity improves performance on various metrics including stock price growth and return on assets. It was also associated with “lower probability of regulators taking actions against the bank holding company”.

Other evidence suggests that women board members literally show up more often than the men do – and furthermore that having more women on boards magically improves the men’s attendance too.

So what can foundations do to diversify in practical terms? Family foundations, virtually by definition, comprise only members of one family. Charity committees of corporations are normally drawn exclusively from the staff.

In the case of a company, the question is linked to the make-up of staff generally – in other words, whether the company seeks, recruits, promotes and retains adequately diverse staff. Much has been written about that elsewhere.

“For any charity board or committee, a good move is to have a formal recruitment process.  Informally recruiting through networks seems to perpetuate homogeneity because “social networks normally are defined by sameness,” observes Rosien Herweijer, co-founder of All On Board, which advises non-profit and foundation boards. Nearly three-quarters of UK charity trustees are recruited that way.

Informally recruiting through networks seems to perpetuate homogeneity because “social networks normally are defined by sameness,” observes Rosien Herweijer, co-founder of All On Board, which advises non-profit and foundation boards. Nearly three-quarters of UK charity trustees are recruited that way.

Limiting board members’ tenure ensures turnover in the board. This sounds like no-brainer, but a study of US foundations found that, though most foundation boards have terms for their members, nearly half have no limit on the number of terms a board member may serve.

One reason that so many trustees are wealthy and retired is that most board positions are unpaid, normally by law. One workaround is to have advisers to the board”, who attend board meetings and are indistinguishable from trustees in their role, but who are paid. I’ve seen that work well.

Another solution is to bring in a “re-granting” organisation that involves the people it aims to help in its funding decisions. One example is the Edge Fund.

A structural fix is to create two tiers within a foundation, separating oversight and governance from operational grant making. In this system, the board decides the foundation’s priorities, when to form partnerships with other funders, how to assess the foundation’s performance, membership of the grant-making committee (including people from the communities intended to benefit from the giving), and so on. The grant-making committee does the detailed work of reviewing each prospective grant, deciding yes or no, and monitoring grant performance.

This model creates space for diversity even when that is impossible on the governing board–— and enables the board to review its own performance. “This is far too rare. So many problems could be avoided if boards step back and look at themselves,” says Ms Herweijer. In fact, the division between governance and operational tiers is a requirement of the Dutch charity governance code.

A stronger variant is to move decision-making to an altogether separate organisation, led by the communities intended to benefit. For example, Lord Sainsbury, the billionaire UK donor, has provided long-term funding to support the creation of several independent charitable foundations in east Africa, overseen by their own local boards. Similarly, the German Freudenberg Foundation was involved in creating and has supported a foundation, the Hildegard Lagrenne Stiftung, led by the Roma and Sinti communities.

Nothing forces foundations and companies to distribute power along with their money. But it is important for empowering those we seek to help, and evidently possible.

______

Pingback: Announcing a rating of UK foundations on their transparency, accountability and diversity |